By Alice Yin and A.D. Quig

Chicago Tribune

(TNS)

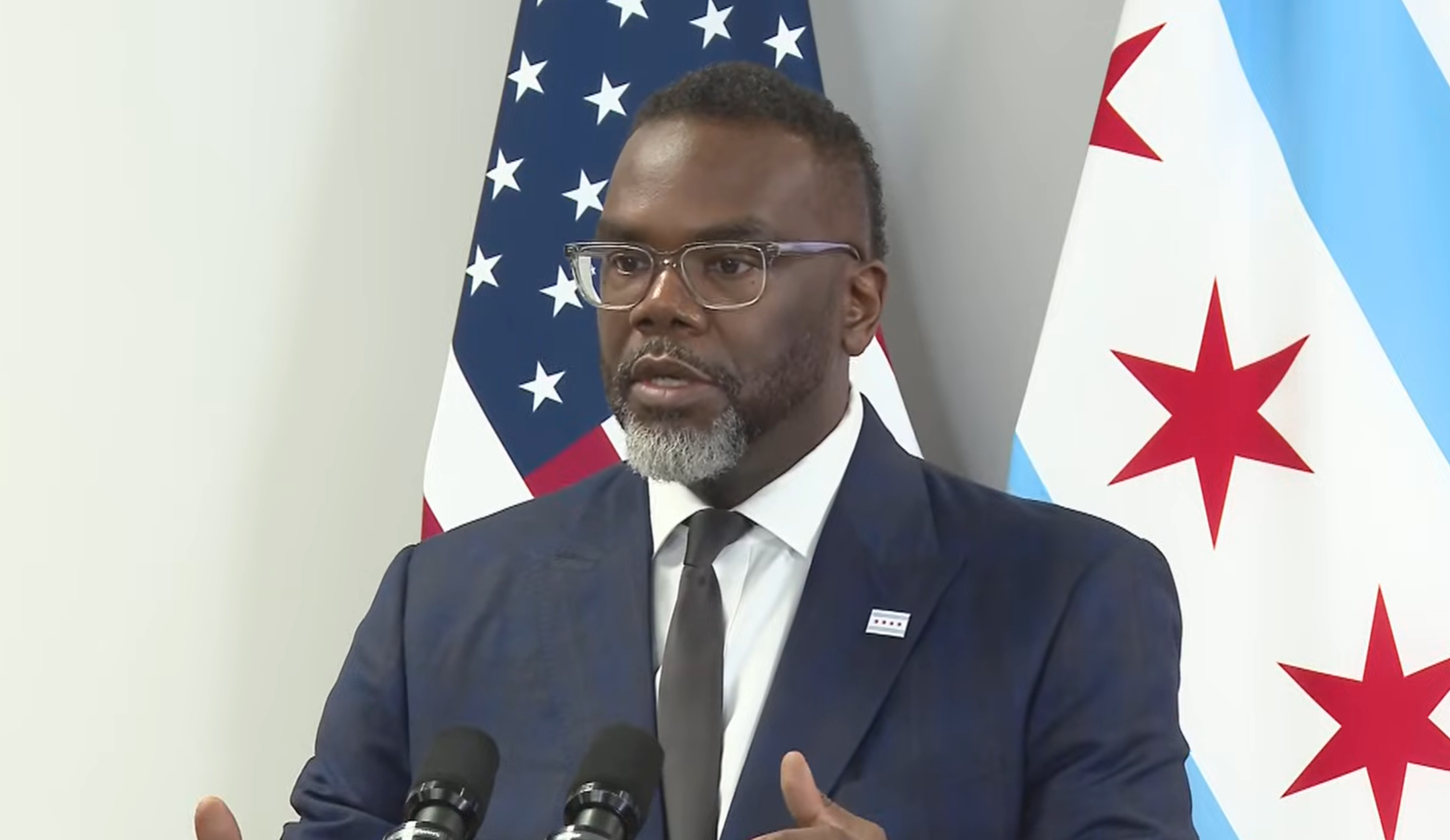

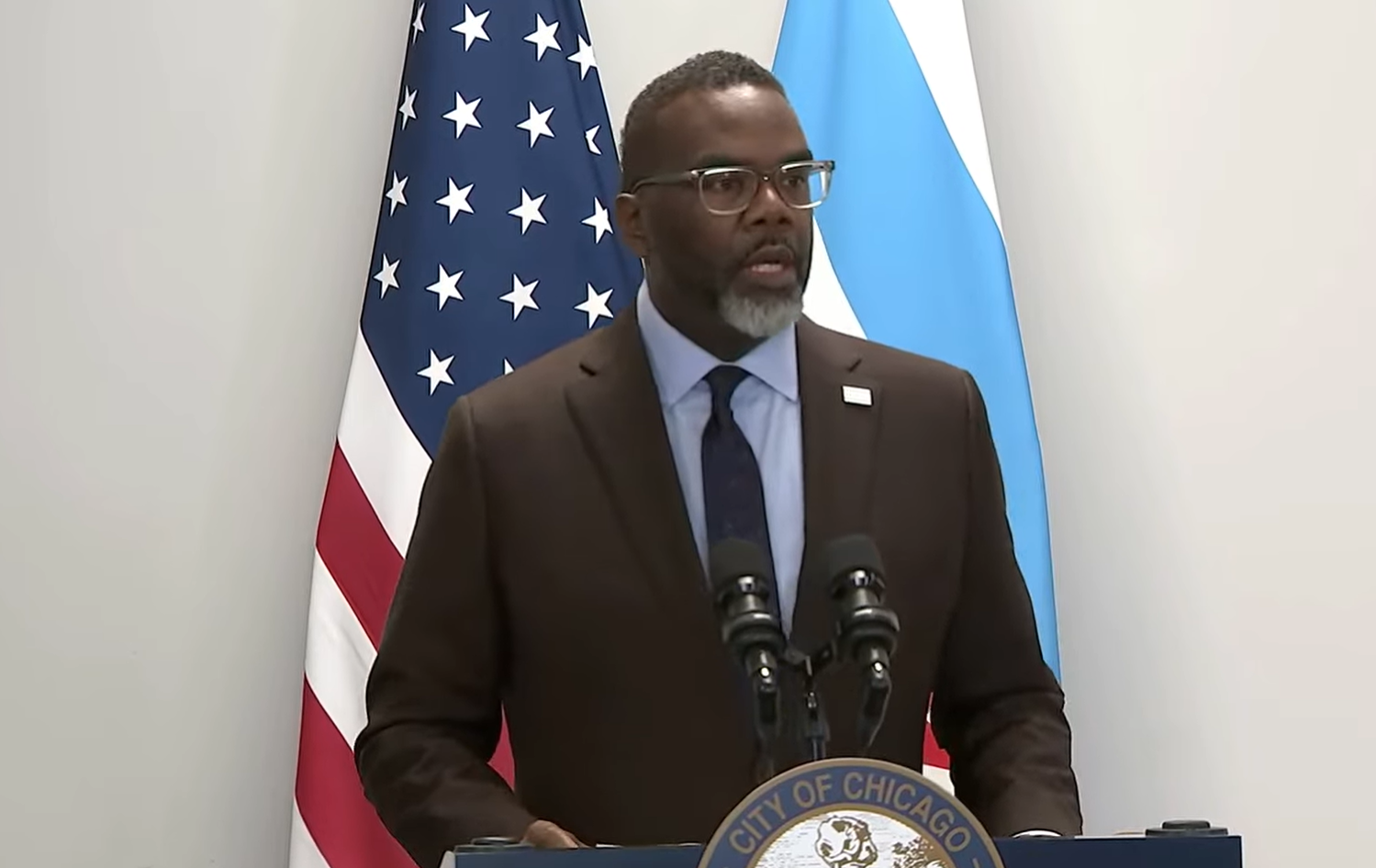

Oct. 30 — A majority of aldermen signed onto a letter Thursday objecting to reinstating Chicago’s head tax and other components of Mayor Brandon Johnson’s 2026 budget plan.

The 28 aldermen said they were “gravely concerned” about what Johnson’s pitch for a monthly $21-per-employee tax on larger companies would do for job growth and companies leaving Chicago. The city’s old head tax, phased out in 2014, was cast as the next frontier in the mayor’s largely stalled tax-the-rich agenda, as he seeks to plug a $1.19 billion deficit in next year’s budget.

“We ask your administration to model alternative budget scenarios that exclude this jobs tax,” the letter said.

Other demands the aldermen laid out include asking the Johnson administration to look at more cuts as identified by Ernst & Young after the city hired the firm this spring to look under the city’s hood to find more savings and efficiencies. The letter calls for representatives from the accounting firm to testify before the City Council’s budget committee to explain why some recommendations were rejected.

Lastly, the council bloc said they were “very concerned” about further borrowing for operating expenses such as back pay for the new firefighters’ contract, saying that “we believe such practices undermine long-term fiscal stability.”

Recommended Articles

Taxes December 17, 2025

Citadel Leaves Chicago Tower as City Alarmed by ‘Job Killer’ Tax

Taxes December 9, 2025

Chicago Mayor Tweaks Head Tax Plan to Target Bigger Companies

Johnson’s team said the city would issue a new bond to make good on $185 million owed in back pay to Chicago firefighters, as well as a $90 million “global” payment to resolve misconduct claims against former Chicago police Sgt. Ronald Watts, among other legal settlements. While that frees up dollars in this year’s budget, it tacks on interest costs in future years—firefighter debt would be paid back over three years, city briefing documents said, and the settlements over five years.

The aldermen signing on were mostly mayoral opponents and moderates but also included Johnson’s handpicked Finance Committee chair, Ald. Pat Dowell, and Ald. Desmon Yancy, a member of the Progressive Caucus, which is supposed to be Johnson’s most ideologically aligned bloc.

Seven of the signees to Thursday’s letter voted in favor of Johnson’s last budget, which eked by in a 27-23 vote: Aldermen Dowell, Yancy, Gregory Mitchell, Stephanie Coleman, Nicholas Sposato, Emma Mitts and Michelle Harris.

A spokesperson for the mayor’s office didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment Thursday morning about the letter. But Ald. Matt O’Shea told the Tribune he could see Johnson staffers on the floor of City Council chambers attempting to pull aside some of the aldermen who joined him in signing the letter.

O’Shea, a mayoral critic, said a budget vote tentatively scheduled for mid-November spooked his colleagues into executing Thursday’s rebuke.

“We’re nowhere near ready for that,” O’Shea said. “We do not have the information we need to vote on what is the largest budget gap in the history of our city. And it was evident the mayor’s office thought that we’re just going to move forward.”

Ald. Nicole Lee, a moderate who signed the letter, said she too has “serious concerns” that a head tax could harm Chicago’s growth.

Lee voted against this year’s budget, and her vote for or against the 2026 package could prove pivotal. She said she also worries that even if the head tax were implemented, loopholes would allow businesses to dodge it, leaving the city with less money than expected.

“But that’s not the only thing,” Lee said. “That’s $100 million. The minute you take something out, we’ve got to come back with something to put back in.”

Johnson introduced a $16.6 billion budget proposal for next year that, besides reinstating the corporate head tax, scales back an extra pension payment and adds other taxes such as a new charge on social media tech giants. But it largely avoids layoffs and does not raise property taxes.

Other one-time tricks—a record $1 billion sweep of tax increment financing funds, refinancing old debt, borrowing money to pay for settlements and labor contracts and a continued hiring freeze—would help cover another significant chunk of the deficit.

The city’s business community immediately tried to put a kibosh on Johnson’s head tax proposal, rejecting the mayor’s framing that it would be an investment in fighting crime. His team has projected $100 million would be raised, going into a so-called Community Safety Fund to partly support some programs that are losing COVID-19 stimulus funds this year.

Johnson’s reaction? “Well, that sounds awfully unreasonable on the part of the business community, and their hard line against funding community safety … doesn’t really reflect the values of the city of Chicago,” he said during a Tuesday news conference.

The results of the initial $3.2 million contract with Ernst & Young were released after Johnson’s budget speech, recommending roughly 100 pages worth of nitty-gritty changes to internal city operations that the firm said could generate between $530 million and $1.4 billion in cost savings or new revenue.

While some updates to fines and fees could happen immediately, the report noted bigger cost-cutting proposals would take years to pull off.

The biggest potential cost saver—optimizing the city’s public safety departments—would take time and “require difficult decisions and complex implementation hurdles,” the report noted, not to mention political barriers.

Among them: cutting the number of firefighters per engine truck from 5 to 4; civilianizing certain fire and police jobs, including cops that perform traffic and parking management; and reducing the hours of the city’s 3-1-1 center from 24 down to 12 hours a day while introducing chatbots. Other tweaks to employee benefits and procurement could save another $200-$450 million.

The city is taking up a few recommendations already, like streamlining city operations and updating ordinances to recoup more money from event-holders for city assistance like road closures and CPD deployment. Ernst & Young recommended the city charge event-holders for estimated upfront costs, then charge a true-up to collect any remaining balance.

The city is also taking a closer look at two other recommendations: slimming its fleet of cars and real estate portfolio. The report noted Chicago’s cost-per-mile for ownership, fuel and services is often higher than the industry and government average and that there are more cars per city worker in Chicago government, suggesting the fleet is too big.

The report also found the city’s real estate portfolio might be underutilized and inefficient. The city could offload some of its office space—anywhere from 200,000 to 300,000 square feet—by encouraging more staff to work from home more often and earn millions from selling groups of city-owned vacant lots or city-owned properties in booming neighborhoods.

Among the costliest leases were a 50,000 square foot space at 231 S. LaSalle, which the city’s inspector general negotiated directly. The space includes 213 seats, but there are only 121 staff, “significantly above standard benchmarks.”

— Chicago Tribune’s Jake Sheridan contributed reporting.

Photo caption: Mayor Brandon Johnson delivers his budget address to the City Council on Oct. 16, 2025, at Chicago City Hall. (Brian Cassella/Chicago Tribune)

_______

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency LLC.

Thanks for reading CPA Practice Advisor!

Subscribe Already registered? Log In

Need more information? Read the FAQs