According to the IRS Oversight Board Survey of Taxpayer Attitudes, 11 percent – or about 20 million taxpayers — believe it is acceptable to cheat on their taxes. The Centers for Disease Control cites published reports that 45 million adults suffer from mental illnesses, and about the same number suffer bipolar conditions. Finally, some 4.5 million American adults believe they have been abducted by aliens.

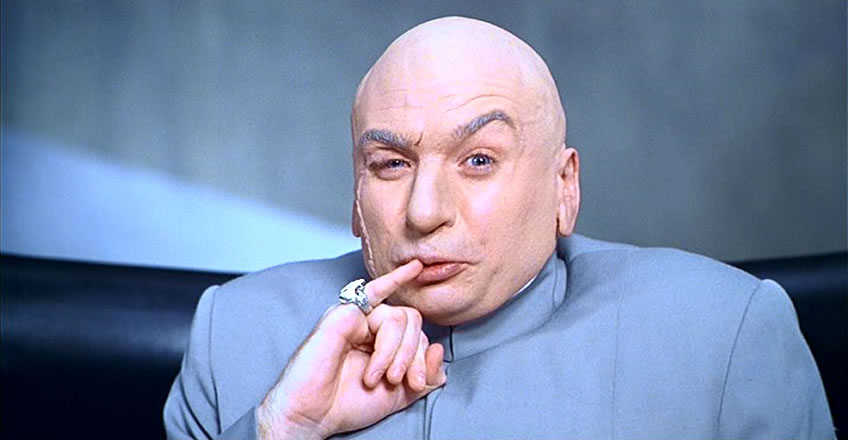

These facts might be interesting, or even amusing, until you realize that these are your clients. The Clients from Hell.

As many as one in five of your clients, by percentages alone, will fall into this category. They are the ones that are chronically difficult to deal with, either by attempting to entice you and your staff to defraud the government, or by presenting behaviors that are disruptive to the firm and to its staff.

It’s a problem I first encountered while working on customer service issues for the General Electric Lighting Division, but have since seen in businesses and industries across the board, including accounting firms. And it is a serious problem. Consider just a few of the issues it can raise:

- There are more problem clients today than ever before. Sociological and psychological profiles of the American population indicate that we are becoming increasingly alienated, frustrated and unable to cope. This is what sociologists call sociopathic behavior — an inability to relate to the demands of everyday life. And it is not just that the population is growing. The research indicates that the relative level of sociopathic and the more serious psychopathic behavior is growing at a rate that far outstrips any population growth. The more people who exhibit this behavior, the more likely it is that accounting clients will exhibit this behavior.

- Market conditions for accounting services contribute to the problem. In spite of record numbers of business startups, growth of the accounting industry has been somewhat modest over the past decade. This means that firms engaging in new business development are more likely to encounter prospects from the pool of people who have left — or been thrown out of — the client bases of competitors.

- Problem clients are expensive. They take up inordinate amounts of time with each engagement, throwing standard fee structures out the window. They are less able to cope with the natural frustrations inherent in the complexities of taxes, regulations and compliance. They contest invoices more frequently, forcing write-downs and lost income. They move from firm to firm. And they contribute to internal overhead costs that can drive profitability to new lows.

- Problem clients contribute to staff turnover. The best new hires won’t work in an environment that is abusive or inordinately stressful, and will simply move on once they have a little experience. You’ll simply be training the best and brightest for your competitors.

- There are hidden costs as well. We know today that increased stress is a contributing factor to alcohol and drug abuse, divorce, emotional problems and other employee problems that can lower the firm’s ability to compete and profit. Problem clients are a significant source of such stress.

- Workflow is hampered. Even among staffers who have learned to hide the stress, the effects are noticeable. Those who routinely must deal with problem clients require time to regroup emotionally — time that becomes wasted productivity. Worse yet, if this time is not taken, the negative emotions generated by the problem client can spill over into successive engagement.

- Times are changing. Where traditional accounting firms have considered the ability to handle problem clients just another part of the job, millennials entering the profession hold no such ideals. They are joined by the rising number of professional women who are demanding – and deserving — a higher level of respect. Reducing the level of abuse that these professionals are expected to take will make them more productive members of the firm. Failure to do this will send some of the best new accountants to other companies and jobs.

If we accept the fact that “clients from hell” are real, and that every firm has to deal with them, the very least that management can do is to establish policies to assist the firm in dealing with such difficult clients.

A New Code of Client Relations

Begin by constructing a new paradigm that allows the accounting and administrative staff to operate under a new set of rules:

- The client is not always right. In fact, the client is generally right no more than half of the time. As a courtesy to respected and valued customers, the company may elect to perform additional services, waive certain fees or otherwise act with generosity. But this is a courtesy extended to the very best clients, not an acknowledgment of any inherent right.

- Bad behavior is bad. Clients are entitled to as much reasonable service as they require to solve problems, assess the performance of their operations, and comply with applicable laws and regulations. They are not entitled to use foul language, make sexual innuendoes, physically touch staff members or otherwise act inappropriately.

- Accounting staffers are hired for their talents, their knowledge and their willingness to contribute to the company. They are not hired for their ability or willingness to tolerate abuse from clients. Staffers are given guidelines within which to work, and within those guidelines they are empowered to terminate abusive telephone calls, refer problem callers to management for resolution, or otherwise end the contact with the client.

- Management will refuse to tolerate problem clients. Management, as a general philosophy, extends its support to both staffers and valued customers. Clients who chronically present problems will be invited to do business elsewhere.

This is a tough and fair philosophy, but presents some concerns from the outset because it empowers staffers at every level. This may at first seem to give too much power to younger, inexperienced and untried staffers.

At the same time, members of management — and particularly the partners — may not give the problem of problem clients much credence. Remember that these are people who were hired and promoted specifically because they did not acknowledge or understand the problem. Many were promoted for their ability to ignore it.

Clients will need to be trained. Some have been accustomed to verbally abusing people all of their lives without ever realizing it. A new working relationship will take time and patience while customers come to understand that — at least with one firm — this behavior is not acceptable.

Good customers will make the transition quickly. They will understand the value of professionals working on their behalf, and the value of having a respectful, professional relationship with the accounting firm.

Real problem clients won’t make the transition. These will need to — and probably insist upon — talking to senior management. When talking to senior management, they will seem reasonable and sane. They will point out how much business they do with the firm, their long-standing relationship, etc. Once management caves in, however, they will return to terrorizing the staff. These clients believe, at some level, that by purchasing services they are also buying the right to such behavior.

It is not important to understand why these clients are abusive, or that some have never in their lives had boundaries set on their behavior. Leave that to the realm of qualified mental health professionals. It is important to understand that these clients are costing more than they are worth, and that the firm is better off without them — regardless of how large their accounting budget may be.

The largest concern about the new code, though, will be the part that empowers individual staffers to temporarily terminate meetings and engagements at their discretion until they can gain the advice of senior management. This is a power generally reserved for partners, and presents two problems. First, there is the fear that some staff members will terminate a meeting simply because they do not personally like the client or because they are having a bad day. Second, there is the justifiable fear among the staffers that they can be fired for terminating a meeting if that action is later questioned.

All of these concerns can be handled through use of an established, written set of rules that define what a problem client is, how such clients should be handled, and what the correct procedures are for terminating an unproductive engagement with the support of management.

Thanks for reading CPA Practice Advisor!

Subscribe Already registered? Log In

Need more information? Read the FAQs

Tags: Firm Management, Income Taxes